World engagement

[an error occurred while processing this directive]Study abroad: An experience like no other for research and language acquisition[an error occurred while processing this directive] Jennifer LeovyNews Office

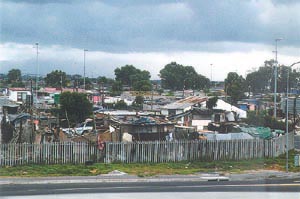

Students who are traveling in South Africa with Professors Jean and John Comaroff will visit places such as Cape Town’s Manenberg township (above). |

“This is going to be an intense experience. Students are going to learn, by direct and indirect experiences, how to look back at Europe and America from an African perspective,” said John Comaroff, the Harold H. Swift Distinguished Service Professor in Anthropology. Comaroff will join Jean Comaroff, the Bernard E. and Ellen C. Sunny Distinguished Service Professor in Anthropology, in leading the course.

The African Civilization sequence in situ is one example of the dramatic expansion of international opportunities for College students, an initiative set forth by John Boyer, Dean of the College, to bolster international study programs and integrate resources for second language acquisition on campus and abroad.

In an era of rapid globalization, College students are pursuing internships, research grants and language immersion programs in their study of other cultures. Jean Comaroff said they will use South Africa as a lens to view the rest of Africa, so that the study of pre- and post-colonial Africa begins in a country “that is creatively remaking itself and is a source of artistic, cultural and philosophical inspiration.”

After a year of planning the 10-week course, the Comaroffs, themselves natives of South Africa, have based the first eight weeks of study and excursions out of Cape Town and the last two weeks in Kruger National Park, a game reserve 1,200 miles northeast of the city. They have called upon a lifetime of contacts with people who have worked and lived in Africa to ensure that the program is safe, intellectually rigorous and culturally enlightening.

“South Africa is a country of optimism and young people and its liberation is very much generational. From that point of view, this is an extraordinary engagement for students in a kind of historical epoch,” she said, adding that South Africans, profoundly aware of their problems, also believe those problems can be solved.

The students will study with the Comaroffs and University graduate students already doing research in Africa. They also will engage with professors and students at the University of Cape Town and the University of the Western Cape. “Chicago’s scholarly intensity will be there, but we want to explode that classroom, taking it into the field,” said Jean Comaroff. Students will visit historic prisons, observe agrarian production and urban geography, and speak with constitutional judges. Some students, including Yarbrough, will do undergraduate research there.

In a country that moved from fascism to democracy in post-modern times, John Comaroff believes that such terms as democracy or globalization, which Chicago students use theoretically, will become tangible in Africa.

“We will ask ‘How do we understand the New World order? What does the world look like from its periphery, from people who are not all in the electronic fast lane and often judged from the outside as underdeveloped?’” said John Comaroff. “This is an effort to engage students in the complexity of these problems without imposing Euro-centric models, which is after all the object of non-Western-civilization sequences–to take the great social legacies and problems and run them up against a very different set of historical, social and cultural issues.”

Boyer views the civilization experience in situ as Chicago’s new paradigm for international education, and as a complement to Robert Redfield’s original inspiration for civilization studies on campus. “We are all islanders to begin with. An acquaintance with another culture, a real and deep acquain-tance, is a release of the mind and the spirit from that isolation,” wrote Redfield, Professor in Anthropology, in his 1947 essay, “The Study of Culture in General Education.”

“One can explore another culture by studying books and artifacts, but there is something about living in a different cultural milieu, making friends with its people, listening to its language, eating its foods and studying its historic sites that is altogether different,” said Boyer.

In addition to seven different civilization courses and plans for programs in London and Bombay, the College offers a growing number of international education options. According to Stephanie Latkovski, Associate Dean of International and Second-language Education, the University offers internships, language immersion programs, academic and foreign language study at international universities, grants for undergraduate research abroad, consortiums that include field research, and research opportunities offered by University professors.

Last year, 259 undergraduates participated in 26 international programs, compared to seven students in two programs between 1983 and 1984. Boyer said by 2006, he expects that one-half of College students will participate in a study-abroad program and one-third in the Foreign Language Proficiency Certificate Program.

“Providing the programs that allow students to reflect on the limits of cultural commonality and the power of cultural difference is a way of broadening students’ personal intellectual horizons at a time when the future forks in the roads of their individual lives are many rather than few. These programs have to be rigorous. They have to be done on our terms, and I think we’ve done that,” said Boyer.

The African civilization course will culminate at the Kruger game field, which was created on consolidated land taken from communities during apartheid. Students will learn about the reserve from game rangers, legal specialists and local communities who, with differing politics, are now contesting land rights.

“Here is a wonderful instance of nature and humanity coming into conflict over control of historical terrain. If anything dramatizes what landscape means, what nature means in the 21st century, Kruger does,” said John Comaroff. “The whole experience will batter our students’ senses. Not one of these students will ever look at the world in the same way.”

![[Chronicle]](/images/small-header.gif)